Inequity is built on a legacy of social, political, and environmental choices made since the formation of our country that continues to play out today. This is a brief and very simplified history of how these choices have become embedded within the infrastructure of our cities and water systems. Much of this section comes from the

2020 Aspen-Nicholas Water Forum Water Affordability and Equity Briefing Document. The report contains citations for much of the text here.

Learn about the Industrial Era (1800s)

The industrial era focused on economic development and growth. Unfortunately, much of this growth also harmed entire social and ethnic groups and environmental health. Cities formed around industries to provide infrastructure to house laborers, create energy, and supply water and sanitation. While private companies initially owned much of the water infrastructure in cities, an 1849 Committee on Public Health noted that “… water is so intimately connected to the health of a city, that the municipal authorities should rank this among the most important of their public duties…”. When laws changed so that local governments could take on debt, they began buying water systems from private companies. By 1910, most major cities owned their water systems and water services were provided throughout a city because the risk of epidemics spread by water-borne diseases, such as cholera, was so great that a city could not risk to fail to provide services to all customers, regardless of race (similar to the shut-off moratoria that took place at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic).

Learn about the Segregated Housing Era (1930s to 1970s)

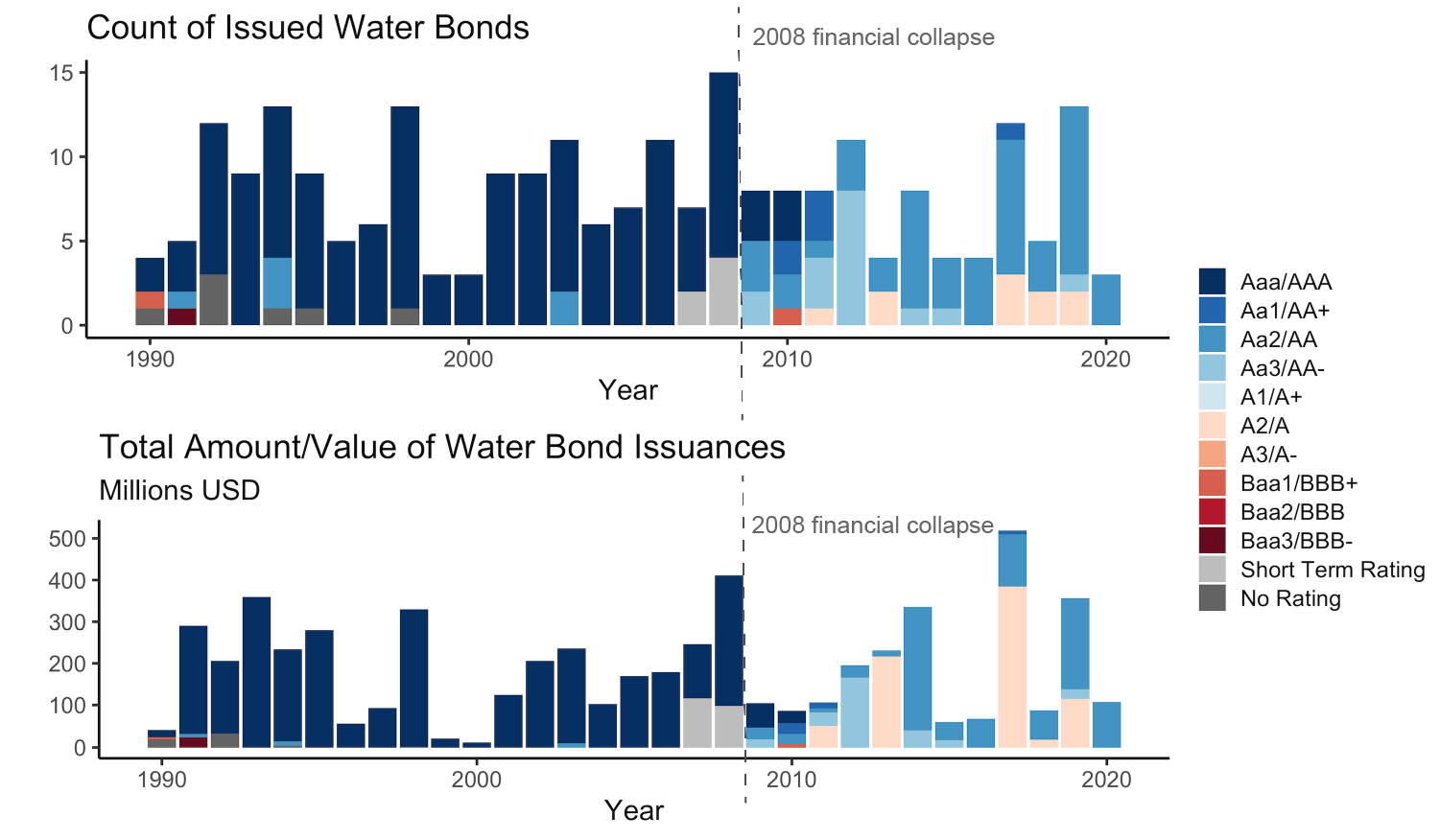

Racial inequity became embedded within water and sanitation systems through housing policies. In the 1920’s, population was growing faster than the housing market could expand. This contributed to the National Mortgage Crisis of the 1930s and the Great Depression. To ensure such a housing crisis would never occur again (at least not until 2008), the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was created. The FHA enabled segregation for over 30 years (1934 to 1968) by guaranteeing the loans of white Americans while refusing to guarantee loans to African Americans or in areas with high African American populations. The systematic denial (directly or indirectly) of various services to residents of specific, often racially determined, communities is known as redlining. Many state and local governments promoted the use of racially restrictive covenants in deeds to prevent the sale of homes to African American families, while private real estate agents used blockbusting to convince white families to leave communities with growing African American populations at a premium and then resold those homes to African American families at inflated prices.

Home Owner’s Loan Corporation maps assigned grades to communities that reflected their mortgage security. Red (redlining) zones were ineligible from government insured loans. Comments often reflect racial reasons as shown for D22 above. Interactive maps are available here: http://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/#maps

These policies encouraged "white flight” to suburbs and concentrations of African American populations in cities became poorer due to redlining policies that kept wealth away. The ensuing disparity continues today. African American incomes are on average 61% of white incomes and African American wealth is 5% of white wealth. Most middle-class families gained their wealth from home equity, homes that many were able to purchase through FHA policies decades earlier. Since African American families were prohibited from buying homes, buying homes with good interest rates, or buying homes in desirable locations, they could not accrue the same wealth. After 1968 FHA technically allowed African Americans to buy homes anywhere, many homes remained unaffordable to those who lacked the baseline wealth.

What does this have to do with water services?

Racial segregation at the scale of neighborhoods and census tracts had implications for the development of local water and wastewater utilities after WWII. As residential segregation increased, municipalities could more easily exclude communities of color from water and sewer services through a practice known as under-bounding, whereby municipalities selectively annexed white neighborhoods into the town’s official boundaries while ignoring African American neighborhoods. This type of under-bounding has occurred across the country. For instance:

- Zanesville, OH did not construct municipal water lines in African American neighbors in the 1950s

- Roanoke, VA did not extend water and sanitation lines to the nearby predominantly African American town of Hollins

- Central Valley, CA rural Latinx communities were discouraged from incorporating and did not receive the infrastructure funds available to neighboring towns

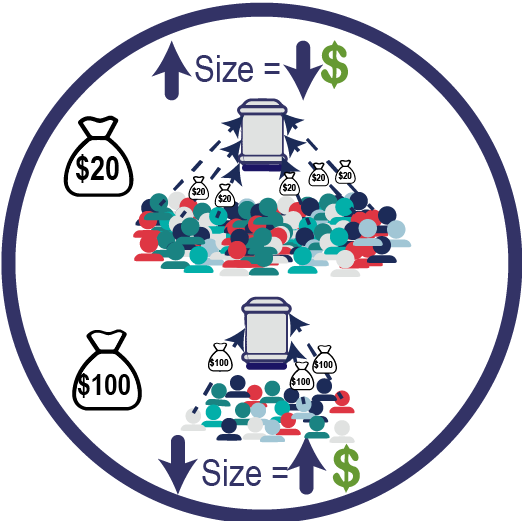

Have you ever wondered while there are so many poor inner cities struggling to afford their water system while surrounded by wealthier suburbs that each have their own systems? At least part of the reason is because white flight moved money to the surrounding suburbs where they could afford to build separate waters systems, removing important financial resources from older utilities. The ability to pay for water systems has become more divided as the racial, and often income, composition of cities became more homogenous (i.e. some systems have a lot of poverty while others have very little). Indeed, in the example of Pittsburgh, 69% of the Pittsburgh Water & Sewer Authority identified as white while that number increased to 94% in the Hampton Shaler Water Authority. As cities have begun to gentrify we see this trend reversing in some areas. Now there are many small, suburbs that are struggling to afford their utilities.

Learn about the Environmental Era (1970s)

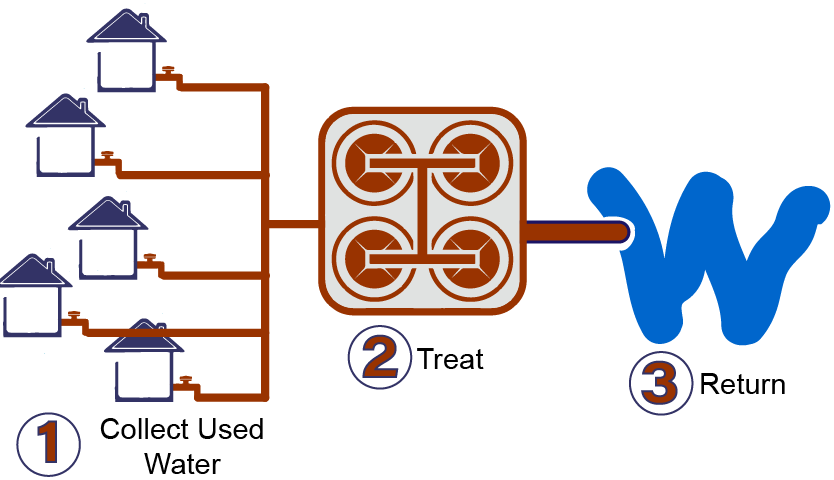

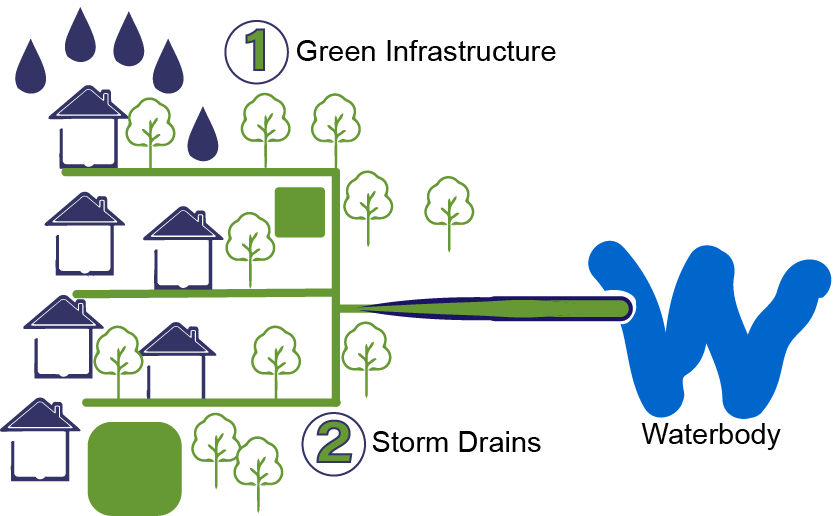

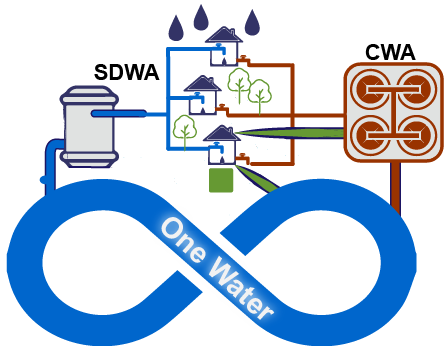

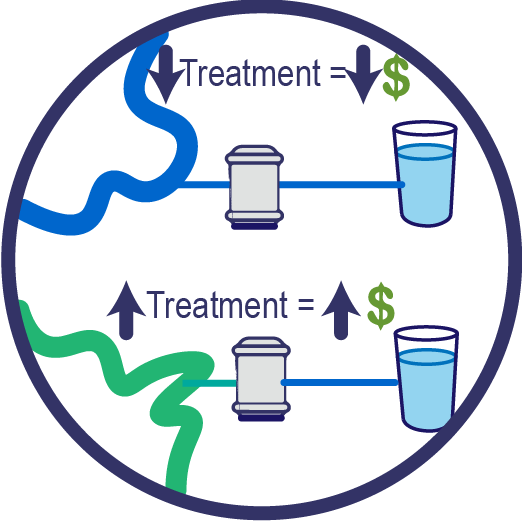

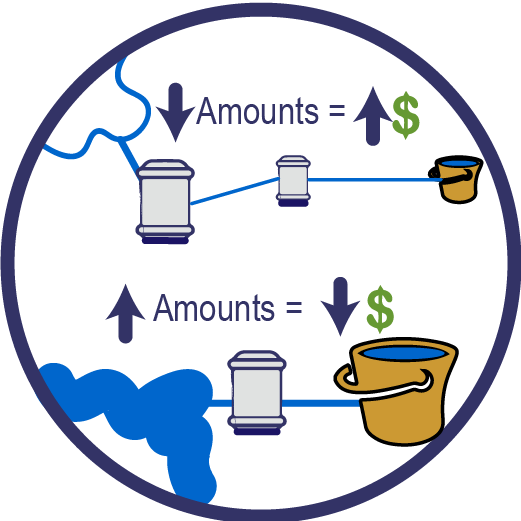

In the early 1970s, Congress passed legislation to protect the quality of our streams and lakes (Clean Water Act in 1972; CWA) and the public health of drinking water (Safe Drinking Water Act in 1974; SDWA). These laws were passed in response to public outcry to 41% of water systems were not meeting health guidelines and jeopardized the health of millions and major rivers were repeatedly catching fire. Both the CWA and SDWA ensure water quality by requiring specific types of treatment to remove specific contaminants (see more).

Both acts included significant federal funding through grants to finance the initial infrastructure needed for local governments to meet these new regulations. Over time, these funds transitioned from grants to loans that have to be repaid. This placed greater financial responsibility onto local and state governments to maintain and upgrade the infrastructure needed for water treatment. While there was an effort to disburse funds equitable, those funds are going to cities (and their utilities) whose capacity to apply for grants and loans were shaped by decades of discriminatory practices. The results is that poorer communities may lack the political power to access safe water supplies and/or regulations are not enforced because the community does not have the financial resources to fix the underlying problem. It remains challenging for small water systems and those serving majority low-income communities to access state and federal dollars.

Learn about the Environmental Justice Era (1980s)

The Civil Rights movement in the 1960s created a unified voice for social justice. Social injustices are prevalent in housing, employment, municipal services, education, and not surprisingly – environmental protection. In the 1980s, the Environmental Justice movement discovered greater evidence that those suffering from environmental injustices were disproportionately low-income and racial minority groups. These communities are more likely to live near hazardous sites, where they are exposed to greater contaminants and suffer the health and economic impacts). Resulting medical bills are expensive, generating further economic disparities. Well known examples include:

- “Cancer Alley” impacts on African American communities by petrochemical manufacturers,

- uranium mining on Navajo lands,

- and pesticide exposure among predominantly Latinx farm workers.

Some environmental inequity is intentional, some began intentionally and is now perpetuated by the inertia of the status quo, and some began unintentionally and continues to be perpetuated.

Environmental injustices start with industry being given the right to pollute before proving harm, rather than having to prove no harm before being given the right to pollute. The negative impacts from industrial pollution are born by the public, particularly low-income and minority communities. Land use controls are

often used to put locally unwanted land uses in minority communities that lack the voice or political capital to advocate for “Not-In-My-Back-Yard.” There is also a history of putting unwanted land uses in minority communities to drive residents out, effectively serving as a “taking” of property. If all communities were given an equal voice and political power, the rate of environmental degradation would likely slow. However, private industries are often the needed employers for many low-income communities, which inhibits many communities from raising concerns as they must choose between employment and health.

Learn about where we are today

The legacy of many yesterdays brings us to today

Water systems are an essential infrastructure within communities. Our water systems were shaped by the legacy of inequality and environmental injustice that have shaped, and continue to shape, the communities they serve. It can be seen in the water crises that have too often made the news:

- In California, drought led to over-pumping of aquifers that left agricultural and rural communities without access to water and some remain without access today.

- The lead crisis in Flint, MI revealed a city-sized utility knowingly provided visibly contaminated water to its citizens, predominantly under-served communities of color.

- Lead crises in Pittsburgh, PA, Camden, NJ, and Newark, NJ continually highlight links between water contamination, poverty, and race.

- The prevalence of perchlorate health impacts for the past 20 years has been overshadowed by growing concerns of PFOA and PFAS in drinking water supplies that wealthy industries have left for communities to pay to clean up.

- The discovery of tropical parasites in Lowndes County, AL due to inadequate sanitation and the widespread presence of raw sewage is unfathomable to many.

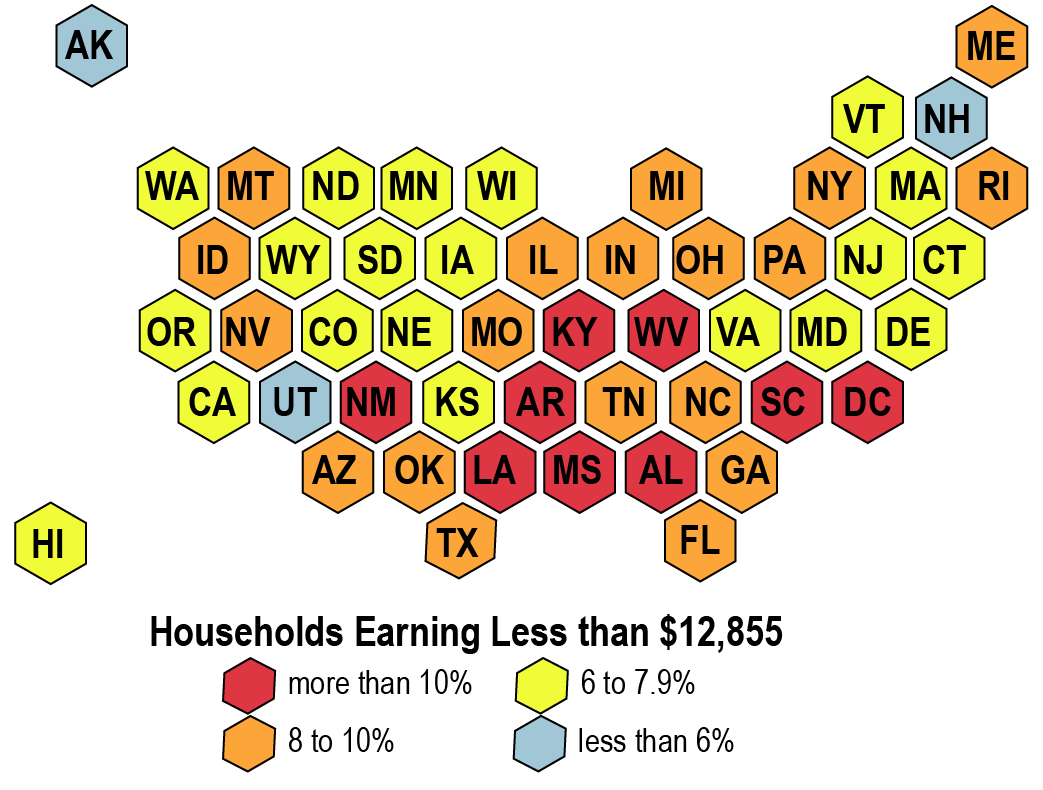

The occurrence of massive water shutoffs in major cities have led to repeated outcries for the human right to water. Racism continues to manifest as white communities get green infrastructure projects while communities of color receive grey infrastructure, and those communities of color that do receive green infrastructure often contribute to gentrification. A warming climate with more frequent and intense flood events disproportionately impact poor, minority communities and agricultural lands. Communities facing the greatest water stress and threat to water security include dis-invested urban areas, rural areas, unincorporated areas, and Native American lands.

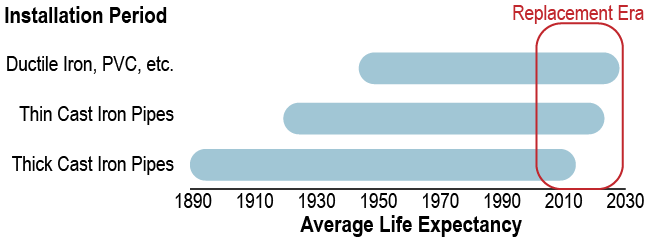

Inequities are embedded within many water systems and it is a "wicked" problem. And there is opportunity as we enter a season of replacing much of our aging infrastructure and revisiting water quality legislation passed more than 50 years ago in light of technology advances and emerging contaminants. We have an opportunity to rethink how we manage water as we modernize our nation's water infrastructure. There is opportunity to provide water services more equitably. The problems of inequity are bigger than water and the solutions need to be too.

;

;