How a graduate student class in King County, Washington (USA) is using the Bridge Collaborative evidence rubric to validate links between pollution, people and wildlife in the Puget Sound.

Phil Levin didn’t quite know what to make of the Bridge Collaborative’s “Evidence Evaluation Rubric” when he stumbled across it at The Nature Conservancy’s Global Science Gathering in November 2018. So, like all good professors, he gave it to his graduate student class to figure out.

Outlined in the Collaborative’s Practitioner’s Guide (and this journal article), the rubric aims to support consistent interpretation of evidence from multiple sectors; be that health, development, or environment.

Phil is Professor of Practice at the University of Washington in Seattle (USA), and the Lead Scientist for The Nature Conservancy’s Washington chapter. His class at the time was looking at environmental issues in the Puget Sound, specifically around the effects of untreated stormwater on its wildlife and indigenous communities. An estimated 75% of the pollution in the Puget Sound comes from stormwater, and there is increasing evidence of the effects of pollutants on salmon, orcas, and other species of conservation and cultural concern. Toxic chemicals in stormwater can also severely impact human health.

For 10 weeks, Phil’s class of eight worked with King County (in which Seattle lies) to build a tool that would help managers at the different stormwater treatment points make better use of cross-sector evidence, to inform decisions or better understand challenges.

Getting Confident

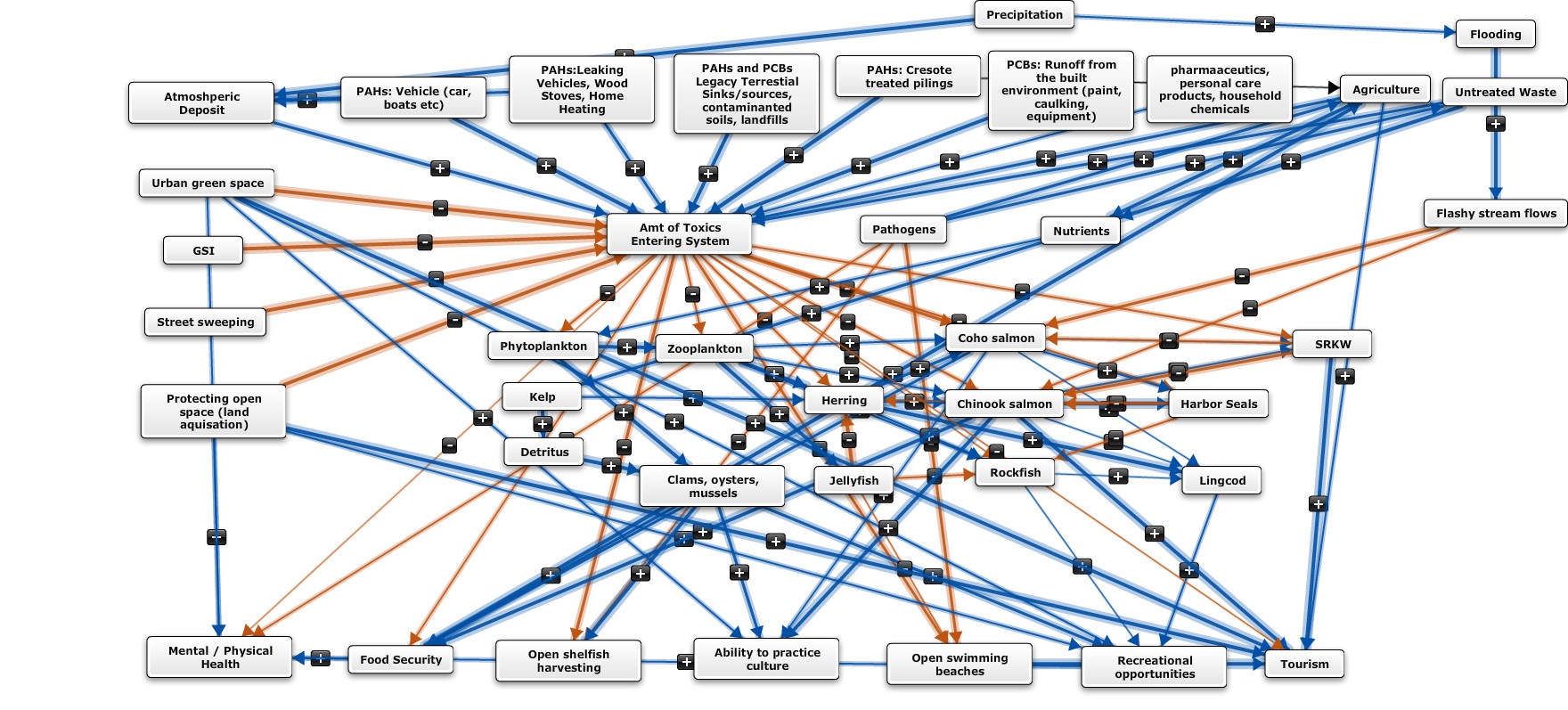

The tool the students built is a web of linkages that outline negative or positive impacts of one element (household chemicals, for example) on another (such as the ability to practice culture).

A visualization of the linkages tool, built using the Bridge Collaborative evidence evaluation rubric.

The students built around 100 linkages within the tool—each one with a diversity of relevant peer-reviewed literature surrounding it. Each student focused on a different sector for the tool, from herring and mental health, to shellfish and plastics.

But how to ensure consistent interpretation of the literature in these different sectors? Enter the evidence evaluation rubric.

The Bridge Collaborative’s rubric helps identify confidence in results chain assumptions across health, development and environmental evidence. It uses four categories of criteria:

- Types of evidence (e.g. multiple/several/limited)

- Consistency of results (the agreement across findings in a body of evidence)

- Methods (those that have been peer reviewed or otherwise broadly supported by a community of practice)

- Applicability (the similarity in ecological, social, political, economic or other relevant conditions between those represented in the available evidence and those in the case to which the evidence is being applied).

These categories collectively inform the assessment of confidence level from low to high.

Phil Levin brings this rubric to life: “We know with high confidence that toxics have a strong negative impact on salmon,” he says. “We have less confidence in the strength of the linkages between toxics and recreation or tourism, for example. There are few studies globally and even fewer for our area. And the linkages are likely quite diffuse.

Why Does It Matter?

At the end of the 10-week period, students presented the modeling tool to representatives at King County.

The rubric has helped outline knowledge gaps (where there is low confidence in an important linkage), highlighted where there is scope to develop the science around specific areas of interest to stakeholders, and ultimately where there are greater opportunities for cross-sector collaboration.

“I can see myself using [the rubric] in my future career,” says Caitlyn O’Connor, one of Phil’s students who focused on the marine food web and how toxics impact each species specifically. “Restoring and protecting environmental resources is a collective effort, one that spans boundaries between biophysical, social and economic elements, functions, and institutions. If I were to work on improving Puget Sound, I would need to be able to work with diverse people, integrate multiple perspectives, and find common ground to achieve our shared objective. This rubric aids in organizing, synthesizing, and communicating scientific information to create one shared evidence base that allows us to discuss potential tradeoffs across sectors.”

Building on the experience of this group of students, Director of the Bridge Collaborative Josh Goldstein thinks applying the rubric in this way could help lay the foundation for a more collaborative future. “One of the major barriers to better cross-sector action planning and evidence use is the way that people are trained from graduate school upwards,” he says. “It reinforces silos—in methods, in awareness, even down to the people we meet and who we know to reach out to. Phil’s use of the rubric is an example of how people are training students in new ways to better understand and help solve connected challenges for people and the planet.”