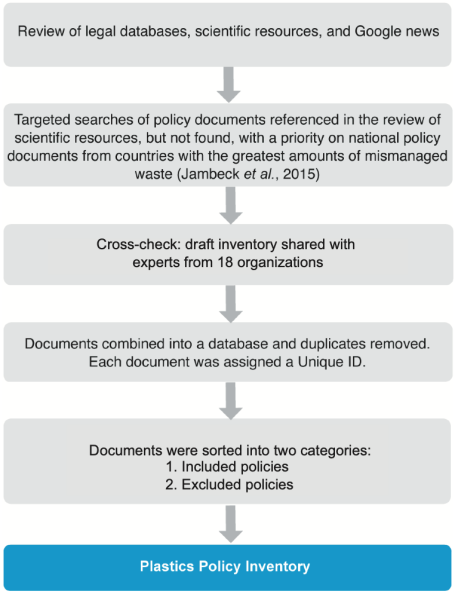

2020 Report: Database Construction (Covering January 2000 Through June 2019)

Step one: Global environmental legal databases for policy documents

In the first step, a team of researchers searched the following international databases containing public policy documents: ECOLEX, InforMEA, and the UN Ocean Commitments site, for the period from January 1, 2000 to July 2019. ECOLEX is an information service on environmental law and is operated jointly by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which independently have their own legal databases. The database combines information from all three partners to serve as a comprehensive source on global environmental law and information. The three organizations receive information and multilateral, national, and subnational policies from governments, academia, NGOs, companies, and members of the public to collate this database. As a result, some geographies with more resources and capacity may have more representation in this database than others. InforMEA is the United Nations Information Portal on multilateral environmental agreements facilitated by UNEP and supported by the EU. This database focuses on multilateral agreements and collects information through CoP decisions and resolution, MEA secretariats and other members, partner organizations, news, national reports, and implementation plans. InforMEA hosts annual steering committee meetings. Its stakeholders include 43 international and regional legally binding instruments from 18 secretariats and welcomes observers from other multilateral institutions. The database does include national level environmental policies as well. Available information suggests that InforMEA collects data through annual meetings and established relationships with stakeholders. As such, certain regions may be more represented than others. The United Nations Ocean Commitments website stores a registry of voluntary commitments made by entities ranging from governments, intergovernmental organizations, civil society organizations, nongovernmental organizations, or corporations, among others, targeted to any or all components of UN SDG 14. The website supports search and filter functions to identify and follow-up on government responses to the plastic pollution problem. Some of these voluntary commitments were implemented through policies, while others were not. Commitments made by governments outside of this conference are not included in the database. These three sites were selected because they provide users with comprehensive and up-to-date access to primary sources (i.e., policy documents themselves) on the international, regional, and national level, and to a lesser extent on the subnational level. In addition, they provide secondary and tertiary resources that describe policies, including newspaper articles, court decisions, and legal literature).

A consistent set of key words was used for the searches (the databases do not support searches using Boolean combinations of terms), as shown in Box 1 below.

The results (i.e., public policy documents) of independent searches by each researcher were combined into one list (stored in an Excel database) unless the title or short description provided by the online database clearly indicated that the document was not relevant (e.g., a policy for sterilizing plastic gloves for surgery). Subsequently, duplicates appearing in multiple searches were removed. Each of the remaining documents was given a unique identification number and retained for screening. This list of documents was cross-checked against the non-searchable Foreign Law Guide database, using the information provided in the database about the legal systems of countries around the world and citations to their legal publications, as well as a list of environmental policies by nation. Foreign Law Guide was not used in future inventory updates.

Step two: Search the secondary literature for policy documents

In the second step, a library of scientific literature about public policies aiming to address marine plastic pollution was compiled, from searches of the following interdisciplinary or legal research databases: Web of Science, Google Scholar, and HeinOnline (legal literature), for the period from January 1, 2000 to July 2019. The Boolean combinations of terms (i.e., search strings) used for these databases included the terms in Box 1 related to plastic pollution, as well as additional terms related to policy that were identified based on terms associated with or descriptors of public policy and governance interventions that could address leakage of plastics. Hence, the first half of the search string consisted of terms relating to plastic pollution and the second half of terms relating to public policy and governance. Based on initial tests, the search string of terms related to plastic pollution was divided into three smaller strings: (1) more general, (2) less general, and (3) “poly” words, all in combination with the same terms for public policy and governance. These three strings were specified in order to target the most relevant articles among a high number of returns, allowing the most relevant articles to be more easily identified among the returns. For example, the string with “poly” words for plastic pollutants returned a significant number of articles related to the chemistry of plastics, which crowded out articles relating to plastic pollution. The three strings used are as follows:

- Most general: (“Marine debris” OR “Marine litter” OR Microplastic OR Microfiber OR Plastic NOT Surge* NOT elast*) AND (Policy OR Govern* OR Institution OR Law OR Regulat* OR Legal OR Intervention OR Infrastructure OR Coastal city OR Mega-city OR Municip* OR Subsidy OR subsidize OR Subsidies OR Ban OR bans OR banned OR Tax OR taxes OR taxed OR Fee OR Fees);

- Less general: (Nylon OR “Shopping bag” OR Styrofoam OR “Synthetic disposable” OR Tire OR Tyre OR “Cigarette waste” OR “Beach clean-up” OR “Coast* clean-up” OR “River clean-up”) AND (Policy OR Govern* OR Institution OR Law OR Regulat* OR Legal OR Intervention OR Infrastructure OR Coastal city OR Mega-city OR Municip* OR Subsidy OR subsidize OR Subsidies OR Ban OR bans OR banned OR Tax OR taxes OR taxed OR Fee OR Fees); and

- “Poly” words: (Polyethylene OR Polymethyl methacrylate OR Polypropylene OR Polystyrene OR Polyvinyl chloride OR Recyclate OR Polymer OR Bioplastic OR Oxodegradable) AND (Policy OR Govern* OR Institution OR Law OR Regulat* OR Legal OR Intervention OR Infrastructure OR Coastal city OR Mega-city OR Municip* OR Subsidy OR subsidize OR Subsidies OR Ban OR bans OR banned OR Tax OR taxes OR taxed OR Fee OR Fees).

The “most general” search string above included two exclusions to further refine for relevant articles—(1) “NOT Surge*” and (2) “NOT elast*”—in order to remove results that address plastic surgery or mechanical engineering papers (“elastic-plastic” response). This exclusion further reduced the number of articles to screen and increased the density of relevant articles reviewed. Using each of the above three search strings and the two exclusions for the most general string, the results were sorted by relevance, non-English articles and those published before 2000 excluded, and one researcher screened the top articles.

For the searches in Google Scholar, the search strings were shortened to address the smaller text box, using either one, two, or three plastic pollution terms plus the string of terms for public policy and governance (altered to utilize the * wildcard on more terms in order to fit to the Google Scholar search box). The resulting shortened strings that were used are as follows: (“PLASTIC WORD”) AND (Policy OR Govern* OR Institution OR Law OR Regulat* OR Legal OR Intervention OR Infrastructure OR Coastal city OR Mega-city OR Municip* OR Subsid* OR Ban* OR Tax* OR Fee*); with the following “plastic words” used: for most general – “Marine debris,” “Marine litter,” (Microplastic OR Microfiber), Plastic; for less general – (Nylon OR “Shopping bag” OR Styrofoam), (Tire OR Tyre), “Cigarette waste,” ((Beach OR Coast* OR River) AND clean-up); and for poly words – (Polyethylene OR Polymethyl methacrylate OR Polypropylene), (Polystyrene OR Polyvinyl chloride), (Recyclate OR Polymer), (Bioplastic OR Oxodegradable OR “synthetic disposable”).

Returns from searches of the three databases (Web of Science, Google Scholar, and HeinOnline) were screened in each case by first reviewing the title and then the abstract of the article, and articles were included in the secondary literature library if they met the following criteria:

- evaluated the effects of public policies introduced with the intention of reducing plastic pollution and/or were expected to have an impact on plastic pollution reduction; or

- primarily provided policy recommendations for reducing plastic pollution; or

- provided information to inform the development of policy recommendations.

Scientific surveys of plastic pollution that do not include a direct reference to an existing public policy in the abstract were excluded, unless presenting a comparison both before and after a policy was introduced. Additionally, articles presenting the results of scientific studies to test the efficacy and efficiency of different technologies for recycling or pyrolysis were excluded as outside the scope of this study.

For the most general search string, the first 500 articles were screened, while the first 300 returns were screened for the less general terms, and the first 130 returns were screened for the poly words. The string with “cigarette waste” only returned 117 results, so all returns were screened. In total, a similar number of articles were screened as to the HeinOnline database: 2,000 for most general, 1,000 for less general, and 550 for poly words.

Finally, from the library constructed, the category for plastics policy effectiveness literature was reviewed (136 articles) by one researcher and all specific public policies described were logged in a database as plastics policy references, together with the sources, for possible inclusion in the inventory if the policy documents could then be located.

In addition to the scientific literature, an ad hoc review of key studies in the grey literature was conducted by two researchers, in order to identify additional policy documents for potential inclusion in the inventory. Studies published after 1999 were identified based on searches of websites for global organizations conducting research on the marine plastic pollution problem (using a single keyword “plastic”), including:

- the European Commission (directed to the following site: http://ec.europa.eu/ environment/waste/plastic_waste.htm, last accessed on June 20, 2019, resulting in review of nine reports, annexes, and staff working documents supporting the European Strategy for Plastics);

- the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (322 returns to a search of the publications page of the FAO website (http://www.fao.org/home/en/) on June 19, 2019, from which non-English documents and newsletters were excluded, and based on a review of titles and abstracts, two reports reviewed);

- the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (four returns to the search of the OECD Library Publications site on April 10, 2019, resulting in one report reviewed),

- the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), (22 returns to a search of the UNEP website (https://www.unenvironment.org/) on April 10, 2019, from which PowerPoint presentations and infographics were excluded, resulting in a total of eight reports reviewed);

- the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) (72 returns to a search of the UNIDO publications database on June 19, 2019, from which workshop proceedings were excluded and based on a review of titles, one report reviewed);

- the World Bank (82 returns to the search of the publications page on the World Bank website (https://www.worldbank.org/) on June 19, 2019, from which Briefs—rather than reports or working papers—were excluded, and based on a review of titles and abstracts, one report reviewed);

- the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (four returns to the search of the IUCN Library system on June 20, 2019, resulting in three reports reviewed

- the World Economic Forum (three returns to the search of the World Economic Forum website (https://www.weforum.org/) on June 20, 2019, resulting in two reports reviewed); the World Resources Institute (WRI) (one return to a search of the publications page of the WRI website (www.wri.org) on June 19, 2019, which was not reviewed); and,

- the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) (860 returns to a search of the WWF website (https:// www.worldwildlife.org/) on June 19, 2019, from which the 100 most relevant were screened by title and abstract, and one report reviewed).

The reports identified in the above ad hoc searches were reviewed for references or descriptions of specific public policy documents describing efforts to reduce plastics leakage, and each reference logged in a database as plastics policy references (based on the description or information available in the text, including the underlying sources where given), for possible inclusion in the inventory. The full log of references to policy documents from the review of the scientific literature and the review of the ad hoc literature, was subsequently reviewed to remove duplicates and references to documents outside of the study period, based on the following rules:

- Policies that were identified from the grey literature without a date that had the same name in the database with a date were assumed to be the same document;

- The newest version of the same policy was added to the database and the outdated version was removed; and

- A grey literature reference to an unnamed policy that had a likely corresponding policy based on country, type of plastic (e.g., plastic bags), and time period in the database were assumed to be duplicates.

On this basis, files of the policy documents referred to in the library of scientific and grey literature constructed were located where possible using the following steps: (1) identify if the reference itself provides a website link to the policy document, (i2) search global databases using the description or name in: ECOLEX, InforMEA, FAOLEX, (3) search for the policy document on government websites of the country or municipality with legislation, or through their respective national gazette, as identified by the Library of Congress’ Guide to Law for each country (4) search the website of the environmental agency of the government of the country where the policy is referenced, and (5) general Google search by name or description of the policy document.

Step three: Conduct a targeted search for policies in top polluting countries

For those countries estimated in Jambeck et al. (2015) to be among the top 50 in mismanaging plastic waste but where no national policy documents had been found and screened into Tier 1 as plastics pollution policies yet a policy had been referenced in the scientific or grey literature, a more targeted and detailed search was conducted as follows: (1) using Google Search to identify any mention of the policy on a range of media (government websites, press releases, nongovernment organization reports, media); (2) searching FAOLEX for the policy document; and (3) searching Google based on available description.

The remaining references to policies identified in the scientific and gray literature in step two for which the policy documents could not be found were stored in a separate database to the inventory, with all available metadata included (i.e., level of intervention—international, national, or subnational, description of the policy, geographic area of jurisdiction, and year enacted) as “Policy documents not found.”

Step four: Cross-check the database with experts

A final cross-check was conducted through consultation with experts. A first request for feedback was sent to a total of 21 experts identified through partners and existing professional networks, of which nine responded.

Step five: Screening the policy documents retained

In this screening process, one researcher reviewed the relevant text of each policy document first (i.e., where the key words were found), and where unclear reviewed the whole document, in order to organize the policy documents into one of four categories in the inventory, as defined below:

- Plastic Pollution Policies [Tier 1]: Policy documents where the intent of the government is clearly the reduction of plastic leakage into the environment at any point in the plastic life cycle;

- Generally Applicable Policies [Tier 2]: Policy documents that may have an impact on the quantity or quality of plastic leakage into the environment, but where the intent of these policies as it relates to plastic leakage cannot be inferred from the document itself; and

- Excluded Policies [Tier 3]: Policy documents where the specific intent and direct impact on plastic leakage at any stage in the life cycle is unclear, ambiguous, or absent, but plastics are peripherally associated with the policy itself.

All policy documents categorized as Tier 1 above were subsequently included in the searchable Plastics Policy Inventory, i.e. a database of “plastic pollution policies”.

2021 Brief: First Update of the Database (Through 2021)

Step one: Search global environmental legal databases for additional policy documents

In the first step, a team of researchers searched the following international databases containing public policy documents: ECOLEX, InforMEA. Results were filtered from the beginning of 2019 through the end of 2021. This allowed the researcher to focus on finding new policies from 2020 and 2021, but also for finding policy documents that may have been added to these databases since the publication of the report. The UN Ocean Commitments were not reviewed because the website had not been comprehensively updated since the publication of the 2020 report.

A consistent set of key words was used for the searches (the databases do not support searches using Boolean combinations of terms), as shown in Box 1 below.

Step two: Search the secondary literature for additional policy documents

The research team conducted country specific literature reviews to develop ten country case studies (Australia, Costa Rica, Estonia, Kenya, Indonesia, Maldives, Malawi, Mexico, the Philippines, Turkey) on plastic pollution and policy in those countries. This search yielded secondary sources that had references to policy documents from multiple countries, including those for which case studies were not developed. Some of these sources are highlighted in the table below.

| Title | In-text Citation (First Author & Publication Year) | Countries Covered |

|---|---|---|

| A Regional Response to a Global Problem: Single Use Plastics Regulation in the Countries of the Pacific Alliance |

Ortiz et al. 2020 | Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Chile |

| Policies, Regulations And Strategies in Latin America and the Caribbean to Prevent Marine Litter and Plastic Waste | Fernandez Garcia et al. 2021 | Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Dominica, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama |

| Tackling Plastic Pollution: Legislative Guide for the Regulation of Single-Use Plastic Products | Excell et al. 2021 | Global |

| Inventory of Global and Regional Plastic Waste Initiatives | GRID-Arendal 2021 | Global |

| Evaluation of Legal Strategies for the Reduction of Plastic Bag Consumption | Chasse 2018 | Global |

Any mention of a national or a subnational policy in these papers that was not already in the database was subsequently searched for using Google and the Library of Congress’ country page, which includes links to legislative databases and gazettes for each country. A researcher did not spend more than 10 minutes looking for any given policy document. Each policy document that was found was given a unique identification number and retained in the internal database. Policy documents not in English could not be extensively screened but were included if the policy title or its description in the literature clearly indicated an approach to plastics specifically.